Executive Summary

Under ASC 606 and IFRS 15, revenue recognition is governed by a five-step model designed to ensure that revenue reflects the transfer of goods and services to customers in an amount that depicts the consideration an entity expects to be entitled to. Among these steps, Step 4 – Allocate the Transaction Price is one of the most misunderstood and operationally challenging.

While Step 3 determines how much consideration is expected from a contract, Step 4 determines how that consideration is distributed across the distinct promises made to the customer. This allocation directly governs revenue timing, margin profiles, deferred revenue balances, and audit outcomes.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive, example-driven explanation of Step 4, grounded in accounting standards but informed by real-world commercial practices and revenue system implementations. It explains the conceptual rationale, formal allocation mechanics, acceptable estimation techniques, special allocation exceptions, auditor focus areas, and system implications—using unique, progressively complex examples to build intuition and technical mastery.

1. Why Allocation Exists (Conceptual Foundation)

By the time an entity reaches Step 4, three foundational determinations have already been made:

- A customer contract exists

- The distinct performance obligations (POBs) in the contract have been identified

- A single transaction price has been determined

The remaining accounting question is deceptively simple:

How much of the transaction price belongs to each promised good or service?

Allocation exists because:

- Customers frequently purchase bundled offerings

- Accounting standards require revenue to reflect standalone economics

- Without allocation rules, entities could accelerate revenue by embedding value in bundles

Step 4 ensures that revenue reflects the economic substance of each promise, not the commercial packaging of the deal.

2. Core Rule (Baseline Allocation Model)

The fundamental requirement under both ASC 606 and IFRS 15 is:

Allocate the transaction price to each performance obligation based on relative Standalone Selling Prices (SSP).

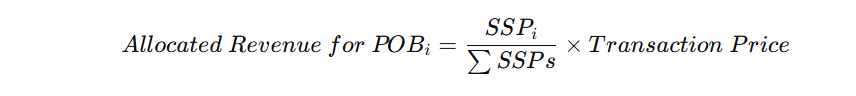

Allocation Formula

This relative allocation model is mandatory unless a specific exception is met. Management judgment is permitted only within the boundaries explicitly defined by the standards.

3. Simple Example – Clean Relative SSP Allocation

Contract Structure

| Item | Standalone Selling Price (SSP) |

| Software License | $1,000 |

| 1-Year Support | $500 |

| Total SSP | $1,500 |

Transaction Price = $1,200

Allocation Result

- License: 1,000 / 1,500 × 1,200 = $800

- Support: 500 / 1,500 × 1,200 = $400

Key Insight

Even if one component appears “secondary,” allocation follows relative standalone value, not intuition or contract emphasis.

4. Why List Price ≠ Standalone Selling Price

A frequent source of error in allocation arises from conflating pricing artifacts with accounting measures.

| Concept | Meaning |

| List Price | Marketing or pricing construct |

| Contract Price | Amount negotiated with the customer |

| Standalone Selling Price (SSP) | Price at which the entity sells a good or service separately in similar circumstances |

Auditors evaluate how SSP is established, not what the price list shows.

5. Estimating SSP When It Is Not Observable

When SSP is not directly observable, the standards require estimation using consistent, supportable methods.

5.1 Adjusted Market Assessment Approach

- Evaluate competitor pricing

- Adjust for geography, customer class, or delivery model

Example

Comparable analytics modules sell for $700–$900

→ Estimated SSP = $800

5.2 Expected Cost Plus Margin Approach

- Estimate fulfillment cost

- Add a reasonable margin

Example

- Implementation cost: $4,000

- Target margin: 30%

→ SSP = $5,714

5.3 Residual Approach (Restricted Use)

Permitted only when:

- One or more SSPs are highly variable or uncertain

- Other SSPs are observable

Example

- Support SSP = $2,000

- Training SSP = $1,000

- Total Contract Price = $10,000

Residual License SSP = $7,000

Residual approaches receive intense audit scrutiny.

6. Allocation When the Contract Includes a Discount

Contract Economics

| Item | SSP |

| License | $10,000 |

| Support | $5,000 |

| Total SSP | $15,000 |

Transaction Price = $12,000

Total discount = $3,000

Default Allocation

- License: 10,000 / 15,000 × 12,000 = $8,000

- Support: 5,000 / 15,000 × 12,000 = $4,000

Discounts are allocated proportionately by default.

7. Allocating Discounts to Specific Performance Obligations

The standards allow deviation from proportional allocation only if all of the following are met:

- Each POB is regularly sold on a standalone basis

- The discount is observable and specifically attributable

- The allocation reflects standalone economics

Example – Discount Applied Only to License

- License SSP = $10,000

- Support SSP = $5,000

- Contract Price = $12,000

Historical evidence shows:

- License sold alone at $7,000

- Support sold alone at $5,000

Allocation

- License = $7,000

- Support = $5,000

Auditors will require documented pricing history.

8. Allocation of Variable Consideration

When variable consideration relates entirely to a specific POB, it is allocated directly rather than proportionally.

Example – Usage-Based Fees

- Fixed subscription: $100,000

- API usage fee: $10 per call (applies only to API service)

The variable amount is allocated exclusively to the API POB.

9. Variable Consideration and the Constraint

Even when variable consideration is allocable, it must respect the constraint.

Example

- Expected bonus: $20,000

- Constrained estimate: $12,000

Only $12,000 enters the allocation process.

10. Multi-Element SaaS Bundle Example

Contract Components

| Performance Obligation | SSP |

| SaaS Subscription | $60,000 |

| Implementation | $30,000 |

| Premium Support | $10,000 |

| Total SSP | $100,000 |

Transaction Price = $85,000

Allocation

- SaaS: $51,000

- Implementation: $25,500

- Support: $8,500

Each POB now carries:

- Its own revenue cap

- Its own recognition pattern

11. Why Allocation Matters Downstream

Step 4 directly impacts:

| Area | Effect |

| Revenue Timing | Step 5 recognition |

| Deferred Revenue | Balance sheet accuracy |

| Margins | POB-level profitability |

| Forecasting | Revenue burn patterns |

| Systems | Event-based accounting |

Incorrect allocation cascades into systemic reporting errors.

12. How Revenue Systems Implement Step 4

Enterprise revenue systems typically:

- Store SSP ranges and policies

- Assign SSPs to each POB

- Apply allocation logic (relative SSP, discounts, variable consideration)

- Persist allocated revenue per POB

- Lock allocations unless a contract modification occurs

Allocation is contract-state sensitive, not recalculated casually.

13. Auditor Focus Areas

Auditors consistently challenge:

- SSP estimation methodology

- Discount attribution logic

- Residual approach usage

- Consistency across contracts

- Allocation changes without valid contract modifications

Unjustified allocation changes are considered high-risk findings.

14. Practical Mental Model

A helpful way to conceptualize allocation is:

“If I sold each promise separately, how much of today’s contract price truly belongs to each?”

Allocation is not driven by:

- Invoice structure

- Sales intent

- Pricing tool defaults

It is driven by standalone economics.

Conclusion

Step 4 – Allocate the Transaction Price is the point at which commercial arrangements are translated into accounting truth. It ensures that bundled contracts do not distort revenue timing, margins, or financial disclosures, and it forms the foundation upon which Step 5 revenue recognition is executed.

When Step 4 is executed correctly:

- Revenue reflects economic reality

- Systems produce consistent outcomes

- Audit risk is reduced

- Financial statements remain defensible

When it is executed poorly, no downstream control can fix the damage.

For organizations operating complex subscription, SaaS, or bundled commercial models, mastery of Step 4 is not optional—it is foundational.